Building a 360° Image Gallery

Note: This documentation is for the old 1.6.0 version of A-Frame. Check out the documentation for the current 1.7.0 version

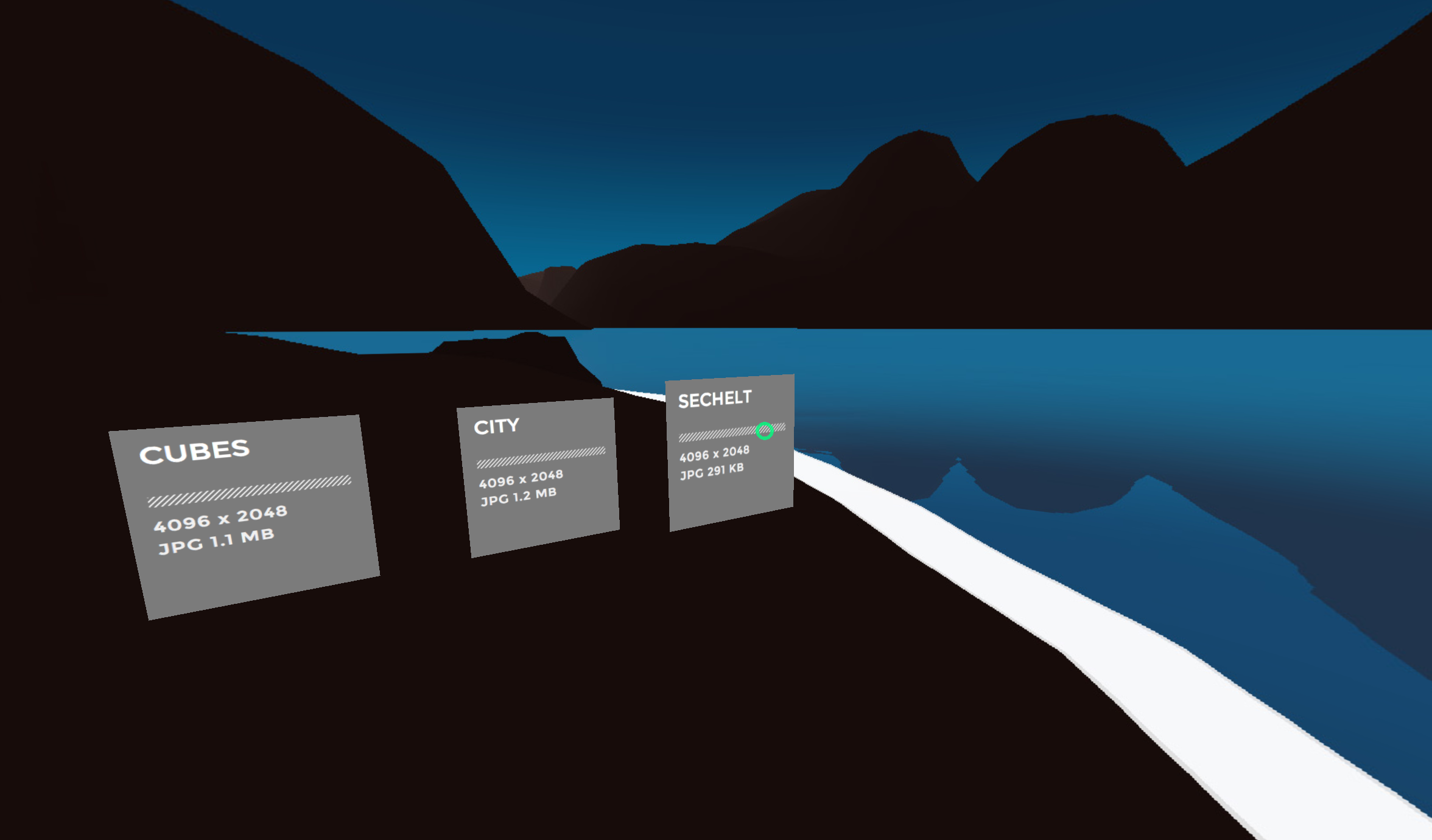

Let’s build an interactive gaze-based 360° image gallery. There will be three panels which the user can click on. Once clicked, the background will fade and swap the 360° images.

This guide will practice three concepts related to entity-component:

- Using the standard components that come with A-Frame.

- Using community components from the ecosystem.

- Writing custom components to accomplish whatever we want.

Not to say 360° images are at all a focus use case of A-Frame, but it makes for an easy example that has a lot of demand as an early use case on the Web.

Skeleton

This is the starting point for our scene.

<a-scene> |

We have predefined:

- Several images to preload in the Asset Management System within

<a-assets>. Note not all our assets must be predefined or preloaded. - Our 360° image placeholder with

<a-sky>. - A cursor with visual feedback using event-driven animations, fixed to the camera.

Using Standard Components

Standard components are components that ship with A-Frame, like any standard library. We’ll go over how to attach these components to entities and configure them from HTML.

We want to build a textured plane to act as a link that when clicked, will change the 360° image. We start with an empty entity. Without any components, any empty entity does nothing and renders nothing:

<a-entity class="link"></a-entity> |

To give our entity shape, we can attach the geometry component, configured to a plane shape. We specify the component data using a syntax that resembles that of inline CSS styles:

<a-entity |

Then to give our entity appearance, we can attach the material

component. We set shader to flat so the image isn’t affected

negatively by lighting. And we set src to #cubes-thumb, a selector to one

of the images preloaded in the Asset Management System. Alternatively,

we could pass a URL for the image:

<a-entity class="link" |

We can continue adding features to our entity by plugging in more components.

Let’s attach one more standard component, the sound component. We want

to make it such that when we click (via gazing) on the link, it plays a click

sound. The syntax is the same as before, but instead we are now using the sound

component’s properties. We set on to click so the sound is played on click.

And we set src to #click-sound, a selector to our <audio> element.

<a-entity class="link" |

Now we have a textured plane that plays a click sound when clicked.

Using Community Components

A-Frame comes with a small core of standard components, but lot of magic comes from the large number of open source community components in the A-Frame ecosystem. We can find community components from places such as npm. We can drop them into our scene and use them straight in our HTML. Components are capable of doing anything and abstract hundreds of lines of code into a single component that can be plugged in via an HTML attribute, like physics!

We’ll go through using four community components:

Community components are generally available through both GitHub and published on npm. An easy way to include components is to use the unpkg.com CDN, which lets us include components hosted on npm as a script tag, even with support for specifying fuzzy versions. We usually just need to know the component’s npm package name and the path:

<html> |

template Component to Create the Links

Currently, we have one link. We want to create three of them, one for each of our 360° images. We want to be able to reuse the HTML definition for all of them.

One solution is the template component, which integrates templating engines into A-Frame at runtime. This lets us do things such as encapsulate groups of entities, passing data to generate entities, or iteration. Since we want to turn one link into three, without copy-and-pasting HTML, we can use the template component.

Ideally, we would do this at build time (e.g., with the Super Nunjucks Webpack Loader), instead of wasting time doing it at runtime. But for simplicity for this tutorial to demonstrate components, we will use the template component. In practice, we’d want to do it with a module bundler such as Webpack.

If we read the template component’s documentation, we see one way

to define a template is via a script tag in <head>. Let’s make our link a

template and give it a name using an id:

<head> |

Then we can use the template to create multiple planes without much work:

<a-entity template="src: #link"></a-entity> |

But then they’ll all be displaying the same image texture and look the same.

Here is where we’ll need a template engine with variable substitution. The

template component comes with simple ES6 string

interpolation (i.e., ${var} format).

To allow each instance of the template to be customizable, we define a

${thumb} variable in the template, which we can pass using data

attributes:

<a-assets> |

The template component has allowed us to not have to repeat a lot of HTML, keeping our scene very readable.

layout Component to Lay Out Links

Because the default position of an entity is 0 0 0, the entities will

overlap. While we could manually position each link, we could instead use the

layout component to do it for us. The layout component will

automatically position its children to the specified layout.

We create a wrapper entity around our links and attach the layout component

using the line layout:

<a-entity id="links" layout="type: line; margin: 1.5" position="-1.5 -1 -4"> |

Now our links are no longer overlapping without us having to calculate and fiddle with positions. The layout component supports other layouts including grid, circle, and dodecahedron. The layout component is fairly simple, but we can imagine in the future, they can get more and more powerful while retaining the same simplicity of use.

event-set Component for Visual Feedback on Hover

Lastly, we’ll add some visual feedback to our links. We want them to scale up

and scale back when they are hovered or clicked. This involves writing an event

listener to do setAttributes on the scale component in response to

cursor events. This is a fairly common pattern so there is an

event-set component that does setAttribute in response to events.

Let’s attach event listeners on our links to scale them up when they are gazed

over, scale them down as they are being clicked, and scale them back when they

are no longer gazed upon. We can specify event names either the _event

property or via the __<id> as shown below. The rest of the properties define

the setAttribute calls. Notice that the event-set component can have

multiple instances:

<script id="link" type="text/html"> |

Remember to add data-src attributes to the link entities to load the full image on click:

<a-entity template="src: #link" data-src="#city" data-thumb="#city-thumb"></a-entity> |

Next, we want to actually set the new background image. We’ll add a nice fade-to-black effect.

The last event-set__click is more complex in that it sets a property on

another entity (our background noted as ID #image-360) with a delay of 300,

setting the texture with material.src. The delay of 300 will allow for the

fade-to-black animation to run before setting the texture.

proxy-event Component to Change the Background

Next, we want to wire up the click on the link to actually changing the

background. We can use proxy-set to pass an event from one entity to

another. It’s a convenient way for telling the background that one of the links

was clicked in order to begin the animation:

<a-entity |

When the link is clicked, it will emit the event also on our background (IDed

as #image-360), renaming the event from click to fade. Now let’s handle this event

to begin the animation:

<!-- 360-degree image. --> |

We set two animations, one setting the color to fade to black, and one setting

the color to fade back to normal. The animation__fade sets to black,

listening to the fade event that we “proxied” earlier.

The animation__fadeback is interesting in that we start it once the

animation__fade completes by listening to the animationcomplete__fade event

that is emitted by animation component when an animation finishes. We

effectively chained these animations!

Wielding components, we were able to do a lot in a few dozen lines of HTML, working on VR across most headsets and browsers. Though the ecosystem has a lot to offer for common needs, non-trivial VR applications will require us to write application-specific components. That is covered in Writing a Component and hopefully in later guides.